#SoundingCrisis @ "What Sounds Do: New Directions in an Anthropology of Sound" - Conference Report

- ANIA MAURUSCHAT

- Oct 7, 2022

- 14 min read

Updated: Oct 27, 2022

In my opinion, the most important direction in any anthropology today certainly is the critical investigation, reflection, and revision of this academic discipline and tradition with all of its exploitation of Indigenous peoples and inhumane atrocities against them in the name of scientific "truth", "civilization," and "progress." This is also the concern of an Anthropology of Sound, as Holger Schulze, principal investigator at the Sound Studies Lab of the University of Copenhagen, propagates it, and this was also one of the main themes of its international conference What Sounds Do: New Directions in an Anthropology of Sound (Sept. 13 to 16, 2022) in Copenhagen (Denmark). The Sounding Crisis research project, which is affiliated with the Sound Studies Lab, investigates the agency of sound practices of Indigenous and non-Indigenous activists and artists addressing the human-nature relationships in times of climate change in Denmark, Kalaallit Nunaat (Greenland), and Australia. It hoped to contribute to this endeavor of deconstructing anthropology in a threefold way: By inviting Dylan Robinson to give a keynote lecture, by presenting the first insights and findings from the field research on the Qilaat, the Inuit frame drum, in Kalaallit Nunaat, and by welcoming to the conference Hivshu, the renowned frame drum singer and story teller from North-Greenland.

I. Keynote lecture of Dylan Robinson

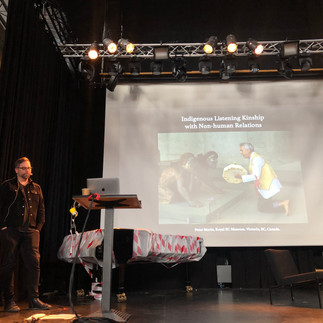

In musicology and sound studies, Dylan Robinson has impressively mastered the challenge of questioning, criticizing and putting into perspective the predominance of Western ontology and epistemology in his seminal book Hungry Listening. Resonant Theory for Indigenous Sound Studies (2020). Robinson is a xwélmexw scholar and artist (Stó:lō/Skwah) and Associate Professor at the University of British Columbia in the School of Music, and Advisor to the Dean on Indigenous Arts in lhq’a:lets/Vancouver, Canada. Thus, it was a great honor that Dylan gave an excellent keynote lecture at the conference What Sounds Do in the main lecture hall of the conference venue Rytmisk Musikkonservatorium (RMC) in front of a large audience. In it he actually focused on how Indigenous songs and sounds have been suppressed and deprived of their agency in past centuries and what it takes to bring them back to life today. In the following summary of my experience of Dylan's talk, which touched me deeply, I have noted down my understanding of it and what seems to me to be most important and inspirational for my own research. Although I am recording my experience and engagement with his lecture through this written text, I don't claim ownership of his knowledge this way. Rather, by recalling it I also want to pay respect to his generosity of sharing his work and knowledge with us.

Dylan's lecture was entitled "Indigenous Listening Kinship with Non-Human Relations" and

structured in three sections in different presentation styles: In the first part, entitled "I. Can you help me understand...", Robinson spoke about the experience of the clashing of different ontologies and epistemologies, whenever he as an Indigenous scholar is asked by non-Indigenous people to explain to them Indigenous concepts and worldviews. As an example he referred to the question "Can you help me understand how Indigenous songs have life?" In my understanding, such a question actually asks for nothing less than breaking down and translating complex Indigenous cosmology, protocol, law, and entire knowledge systems into palatable bits and pieces for non-Indigenous people. What it requests is to make an Indigenous worldview "plain and simple" for a Western worldview, which of course implies no real dialogue between equitable partners. As I understand it, a real dialogue would mean real effort on both sides towards a better understanding of their differences - and possible commonalities. Probably therefore Dylan also writes and speaks at some incidences in his mother tongue Halq’eméylem to advocate for such an equal status and for the recognition of this endangered language. To me it seems that at the same time in doing so he also confronts Westerners with the experience of the limitations of their understanding and the frustration of being excluded, as it is the norm for minorities in predominantly white Western contexts.

For example, Dylan also entitled the second part of his lecture "II. shxwelí li te shxwelítemelh xíts' etáwtxw", without translating it. In this theoretical and historical section he spoke about the differences between Western and Indigenous onotologies and the ramifications which colonization had for Indigenous peoples in this regard:

"Indigenous people continue to contend with Western ontologies that have come to define the boundaries of life and being. We contend with theses externally—through conversations with museums, in educational contexts, and with government policy of the settler state—and at times, we contend among ourselves with the absence of knowledge that has resulted from the long-term, explicit attempts to erase our varied practices of relation with non-human beings through colonial education and government policy. We contend with the words animism and fetishization that arose out of others’ attempts to comprehend how Indigenous ontologies affirm life as it lives variously in spoken words, in stones, in skies, in the land, and in the materiality of the world."

He stated, that due to this holistic understanding of life, which goes far beyond Western notions of the word "life", Indigenous individuals and communities have continuous pushed agains Western legal frameworks. Their perseverance eventually lead to rivers, mountains and whole regions being granted similar rights than human rights. The recognition of environmental personhood and non-human rights is crucial for Indigenous peoples, Dylan explained in his talk, because it enables them to "up-hold their responsibility to their non-human relations and ancestors" effectively and "to maintain the quality of the life of their lands as kin". Nevertheless, the idea of enforcing legal status for rivers or mountains only evolved as a result of the struggle with a Western understanding of property and ownership, I would think, that was imported to the American continent by white settlers in the last centuries. Before that, I assume, it was unnecessary because it was a matter of course. A white settler who argued in support of Indigenous peoples' demand for such a legal status of nature, long before the ubiquitous talk about the Anthropocene started around the year 2000, and who Dylan also quoted in his talk, was the law scholar Christopher D. Stone. In his influential article Should Trees have Standing (1972) he stated:

"It is no answer to say that streams and forests cannot have standing because streams and forests cannot speak. Corporations cannot speak either, nor can states, estates, infants, incompetents, municipalities or universities. Lawyers speak for them, as they customarily do for the ordinary citizen with legal problems."

Following the line of Stone's argument, that rivers and mountains have standing although they cannot speak, Dylan argued that Indigenous songs equally have life and standing for their "owners" respectively relatives or kin. As I understand it, their powerful way of being alive in an Indigenous perspective threatened the white missionaries, colonizers, and settlers in the 19th century so much, that they forbade them in the context of the so-called Potlach Ban, which was active in Canada from 1885 to 1951. This law aimed at the extinction of Indigenous cultures to enforce the assimilation of Indigenous peoples to the Western way of life. As a reaction to this suppression proponents of the so-called salvage ethnography started around the same time collecting Indigenous songs by recording them with phonographs on wax cylinders, Dylan explained. In his words, due to these ethnographic recordings, which nowadays can be found in collections of museums and archives all over the world, Indigenous songs "continue to live". However, the way they are alive in the "carceral" spaces of museums and archives, as Dylan calls them, but also in compositions like for example the opera Louis Riel (1967) by the contemporary Canadian settler composer Harry Somers (1925 - 1999), is an artifical and violent way which disconnects these songs and their traditional "owners" respectively relatives or kin harmfully, Dylan argued. Therefore, In recent years there have been developed by Indigenous peoples as well as museums different strategies of repatriation of Indigenous songs, for example through museums granting Indigenous communities digital access to their songs.

Although this repatriation through granting access is one important aspect of redress, Dylan strongly argued for another kind of work which is in his opinion additionally required to restore the relationship of Indigenous peoples with the more-than-human life of their songs and lands. Thus, in the third section of his talk, entitled "Reconnecting Kinship", Dylan illustrated how to foster reconnection through art and centre Indigenous listening kinship by introducing the audience to the work of the Tahltan Nation artist and curator Peter Morin, specifically to his work NDN Love Song.

Morin, who "has always centred song as an intimate form to reconnect with ancestors (meaning Indigenous songs, A.M.) incarcerated in museums who have been disconnected by great distances from their families across oceans and continents", as Dylan stated, created NDN Love Song as a so-called "score for decolonization" for the ongoing, touring exhibition Soundings: An Exhibition in Five Parts, which Dylan curated together with Candice Hopkins. Morin's score for decolonization consists of seven videos respectively “drum portraits,” which he created when he visited the drums in the Royal British Columbia Museum’s collections. Each drum represents "someone that Morin has loved in his life, where the love has not been able to be fully expressed" (exhibition text). Dylan concluded his talk by playing one of these "drum portraits" videos of Morin's NDN Love Song on the big screen in the background, while reading out loud in front of it a poetic report about how he accompanied Morin at one of his first visits to the museum. While watching Dylan reciting in front of the video it seemed to me as if by holding, touching and moving the drum, Morin reconnects to the life of the drum and collapses the distance the museum has created between kin through incarcerating the drum in a filing cabinet, out of reach for its traditional "owners" respectively relatives or kin. According to Dylan Robinson, NDN Love Song by Peter Morin is a way of healing the trauma of suppressed sounds because it "activates a form of repair, an intimate experience of intimacy, connecting ancestors with viewers through intertwining the sonic, haptic and proprioceptive." Through his touching and impressive talk and especially also its artistic ending, Dylan, in my opinion, managed very well to convey to his primarily European (or even primarily Danish) and yet very attentive audience an idea of "how Indigenous songs have life".

II. The Enduring Power of the Qilaat or the Inuit Frame Drum as the Key to the Universe

It was my honor and pleasure that Dylan was also the respondent to my presentation of the first findings and insights from the field research trip of the Sounding Crisis project in Kalaallit Nunaat from June to September 2022. In my presentation I focused on a different way of reclaiming the agency of the Qilaat, the Inuit frame drum, and bringing its legacy back to life.

At first I reported about my own struggle to come to terms with my positionality as a white European sound studies researcher in Kalaallit Nunaat and how my reflections resulted in the development of an ethical and responsible concern regarding my research methods and data management, which also can be summarised as a #BeFAIRandCARE approach. Thus being concerned with decolonizing methodologies and inspired by the German tradition of the original sound radio play from the 1970s, I presented thereafter the work in progress of my two-part audio paper on "The Enduring Power of the Qilaat" as I call my findings about the Inuit frame drum. Although I researched, prepared, organised, recorded and cut the interviews about the Qilaat, which I made with Indigenous as well as non-Indigenous experts and experts of mixed ethnicity in Kalaallit Nunaat , both parts of the audio paper will contain a minimum of texts from me. Instead, most of the time will be entirely devoted to the original recordings of my interviewees, drum singing and nature sounds. Thus, I aim at giving as much agency as possible to my interview partners and their statements as well as to the sounds of the Qilaat and nature itself.

In the first part of this audio paper presentation I focus on the recognition of the Qilaat as an intangible cultural heritage of the humanity by UNESCO in December 15, 2021. The process for enlisting was initiated in 2010 by the renowned drum dancer Anna Kûitse Thastum (1942 - 2012) from Kulusuk in East Greenland. During my research I was told that the reason why she pushed this application so much, was because she knew that her people, the Inuit of Kalaallit Nunaat, would need the Qilaat to survive. For Inuit, activating the tradition of frame drum dancing and singing is maybe the most important way to reconnect to their past before the Danish-Norwegian colonization started in 1721. It is through the "heartbeat of the drum" that they "connect to the heartbeat of their ancestors", as the frame drum singer and story teller Hivshu at the conference explained the way that the songs are alive for the Inuit. (see below)

The Greenlandic Inuit's understanding of their frame drum as a living being as well as a life force, which was also used by their angakkoqs, their shamans, probably must have massively threatened Danish-Norwegian missionaries of the 18th and 19th century, as the ex-priest Markus E. Olsen claims:

"The sound of the Qilaat was connected to all life, to the rhythm of the universe, and also in regard to how humans interact and resolve conflicts: They always used this sound, the sound of the heart and our ancestors. It is the voice of nature. The missionary Hans Egede saw this and realized that it was a danger to his mission. Therefore, he forbade its use at church because he understood that taking away the Qilaat was a way to break the people’s way of understanding the universe.”

In Greenland never existed an official law like the Potlach Ban in Canada, which forbade the use the Qilaat officially. Nevertheless, the missionary Hans Egede and his sons as well as other missionaries strongly opposed it. They not only considered it heathen but also associated it with evil forces and tried to forbid the sounding of the Qilaat through physical punishment and other measures, which also seems to have let in the Indigenous population to self-censorship and the assumption, that it is officially forbidden, still even today. In fact, the Qilaat still has a special status at the Greenlandic church and cannot be applied as a normal liturgical instrument in services like the organ or the piano. The case of Olsen, who challenged this ideological legacy from colonial times, is the topic of the second part of the audio paper presentation. There I focus on the scandal he caused when he had the Qilaat applied at church in Nuuk on June 21, 2022, the 37th national holiday of Kalaallit Nunaat. The service he held was broadcast live via the national public radio KNR all over the country. Thus, also the drum singing after his sermon was broadcast live all over Kalaallit Nunaat, for which he had not officially asked the bishop for permission, because he is convinced that his request would have been declined. The next day he was suspended and eventually dismissed on August 12, 2022. In the audio paper, the ex-priest and his supporter Aleqa Hammond, a former prime minister of Kalaallit Nunaat, share their point of view, according to which Olsen's dismissal was a highly complex and political case. Remarkably, though, the sound of the Inuit frame drum plays an important and powerful role in this political case as it serves as a symbol of the fight of the Greenlandic Inuit for regaining their identity, for reconnecting with their ancestors and nature, and for decolonizing the mind.

In the context of my research project this political meaning and use of the Qilaat is of special interest because of its connection to Inuit cosmology and the way Inuit relate to their non-human kin. In my interview with Olsen in Nuuk, I asked him if he sees a connection between the Qilaat and climate change and he replied:

"If we cannot hear the heart of nature, an imbalance will occur. To live in balance, people must be able to hear and understand the sound of the Qilaat. It is the same sound as the sound of the heart, the spirit. If we want to create a nature that heals itself and where everything is in balance, it is time that we hear the sound of the heart, which is in the sound of the Qilaat."

To my delight Olsen also attended my conference presentation in Copenhagen on September 14, 2022, wearing a t-shirt that his brother Lars K.S. Olsen has designed and which can be ordered online. On this t-shirt, one could read the core message of Olsen's act of resistance against traditional church rituals in Kalaallit Nunaat: On the back, it asks Greenland to emancipate itself from the former status of a colony, because, according to Olsen, despite Greenlandic self-rule since 2009, church leaders and many Greenlanders are still stuck in a colonial mind-set. Therefore, on the left side of the front of the t-shirt it calls for decolonizing. Around his neck, Olsen wore a Qilaat as an amulet.

On the right side in the front of the t-shirt, one also could see the image of two arctic foxes fighting, an Inuit adaption of the famous native American legend of the two wolves. It are these timeless, universal values of this Indigenous legend which the former priest Olsen feels committed to, as he himself stated.

On October 5, 2022, Olsen declared his candidacy for Folketing in the election on November 1, 2022. As one of the candidates of the Greenlandic social-democratic party Siumut he runs for one of the two Greenlandic seats in the Danish parliament. He wants to focus on foreign affairs and security policy in his work as a politician, who is concerned with the goal of true independence of Kalaallit Nunaat from Denmark, at the press conference, where his candidacy was announced, Olsen - of course - wore around the neck his amulet of the Qilaat.

III. Hivshu Singing Live to the Frame Drum

Olsen brought with him to the What Sounds Do conference also his friend Hivshu, the renowned drum singer and story teller from the most-Northern part of Greenland, who lives in Sweden. His Inuit name Hivshu means "The Voice of the Arctic," and at the conference he sang two songs, embedded in several stories and wisdoms related to the Qilaat. In accordance with Inuit cosmology he considers the Qilaat primarily as an expression of consciousness ( in Inuit comology called "sila") and not as a simple drum, as anthropologists mistakenly thought, as he states in the video (see below). Thus, by applying the Qilaat at the conference he wonderfully created the experience in what way "a song has life", to quote Robinson. As Hivshu explained at the beginning, he also doesn't "perform" when he sings to the Qilaat, as performing is for the "ego" and "the show." What he does instead when he sings to "the heart beat of the drum", according to his Indigenous understanding, is singing for the ancestors and reconnecting with them.

Hivshu's other name is Robert E. Peary II, as he is also named after one of his ancestors, his great-grandfather Robert E. Peary, the US-American explorer who spent 23 years in the Arctic and discovered the North Pole on April 6, 1909. Therefore. Hivshu is also one of the three protagonists of the feature-length documentary film "The Prize of the Pole" (2007) by the Swedish director Staffan Julén. In this movie he travels from his hometown in North Greenland to the US to research the history of his great-grandfather, and the little Inuk Minik Wallace. In 1897 nine-year-old Minik together with his father and four other Inuit was brought by Peary to New York City. There the Inuit were first exhibited to the paying masses and then studied by the anthropologist Franz Boas and his assistants at the American Museum of Natural History, where eventually most of the other Inuit died because of diseases. Even the skeleton of Minik's father was displayed in the permanent exhibition of the museum, where Minik painfully discovered it, although he had been made believe that his father's corps had received a real, appropriate funeral. During his research trip Hivshu discovers the tragic fate of Minik and the other Inuit and their exploitation through Peary and the US-American anthropologists and museum staff. Thus, Hivshu at the end of the documentary has to come to terms with the legacy of his own family history, which encompasses Indigenous as well as non-Indigenous ancestors. In this context it was especially touching that at the conference in Copenhagen, Hivshu shared with the audience songs about forgiveness and healing.

It was an extraordinary honor to welcome Dylan Robinson, Markus E. Olsen and Hivshu in Copenhagen. I acknowledge with gratefulness their effort to travel from far away places to our gathering and their generosity to share their precious knowledge about the agency of the sound of Indigenous songs with us. In addition, I also thank the organisers for their great work, the funders for their financial support as well as the participants for their interest. This altogether made the conference an unforgettable experience of what sounds can do to create a less harmful, a better and a hopeful way of encountering one and another in the future.

Comentários